Getting It Right

Advice on what we see as the really key steps to ensuring your partnership ‘does no harm’.

On this page

There are a huge number of benefits to setting up a school partnership but there are also potential risks. As with all international engagements, it’s vital that we ensure school partnerships follow the key principle of ‘doing no harm’.

It can be hard to really ensure we’re doing no harm because it requires us to step out of our own skin and look holistically at what we’re doing, encouraging challenging and uncomfortable feedback, and really scrutinizing what possible unintended consequences there might be behind our good intentions.

This chapter gives advice on what we see as the really key steps to ensuring your partnership ‘does no harm’.

[Picture: 25th Stirling (Dunblane) Boy’s Brigade, partnered with Likhubula province]

Back in 2012 we asked around 200 Malawian then 200 Scottish organisations what principles made for a successful partnership.

We collated all the answers we received and were excited to find that we were getting the same answers in both Malawi and Scotland, and that these same principles were reinforced by some of the world's leading academics in this field and some of the largest multi-lateral agencies.

From these, we agreed 11 Scotland-Malawi Partnership Principles.

PARTNERSHIP PRINCIPLE CHECKLIST

Planning and implementing together;

Appropriateness;

Respect, trust and mutual understanding;

Transparency and accountability;

No one left behind;

Effectiveness;

Reciprocity;

Sustainability;

Do no Harm;

Interconnectivity;

Parity.

The SMP and all our members are accountable to working within these principles.

Amy Blake, CEO of Classrooms for Malawi comments,

“ ”Amy Blake, CEO of Classrooms for Malawi.“Sustainable school partnerships work when they are based on equitable relationships with strong foundations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Classrooms for Malawi were able to carry out the planned activities between partner schools without the need for volunteer travel”

We really encourage all school partnerships to commit to working within these principles, ensuring this isn’t just a box-ticking or semantic exercise but really drives behaviours, with each side able to challenge the other.

Do embed these Principles within your Partnership Agreement.

Regularly review your Agreement with both partners encouraging honest and challenging feedback on both sides.

Beath High School partnered with Mapanga and Njale Primary Schools said,

“ ”Beath High School.“We, in Scotland, are always impressed by the creative methods employed by our Malawian friends to overcome day to day problems… There is a great deal of support from our colleagues in Malawi, especially in these pandemic times. The partnership has demonstrated that we are all in this together.”

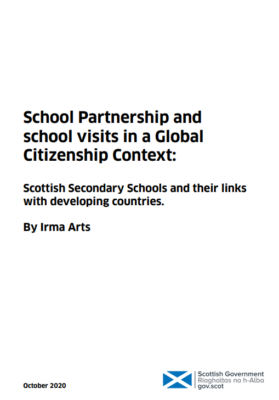

The Scottish Government-commissioned study looking at: ‘School Partnership and school visits in a Global Citizenship Context’ reflected that:

“ ”“…schools should be aware of and take into account issues of inequality, dependency and reinforcing stereotypes. The research showed that teachers seem to be very aware of issues of inequality and dependency and try to navigate having a relationship based on mutual learning with providing support for their partner school.

This support is often thought through and based on the requests and recommendations of the partner school. However, there can be unintended impacts as well as a feeling of powerlessness in partner schools or organisations that will need to be considered and discussed beforehand.

A potential danger lies in reinforcing narratives and practices that are so common that they are not necessarily questioned. The way visits for example were portrayed in pictures and blogs can paint a narrative of the Scottish pupils “helping” the poor and reinforce certain stereotypes of the African continent.

The drive to improve education in the partner country could obscure the necessity for a critical reflection on development, power and poverty.”

The first of the report’s recommendations is for schools to:

“ ”“Start with global learning, not partnerships.

This is a general recommendation for both schools and organisations involved. If the aim is to raise awareness about global issues, partnerships, and specifically peer-to-peer contact, can be a vehicle to start a conversation on these issues, but this will need more than just ‘coming in contact with other cultures’ and asks for the development of critical understanding.

Developing links, organisations and schools should be aware of and take into account issues of inequality, dependency and reinforcing stereotypes.”

The report encourages teachers and learners to invest in building strong foundations, with critical understanding of related issues of inequality, before starting a school partnership. This understanding is perhaps the best preparation for navigating some of the challenges and key decisions which might then come up in a school partnership.

We know that establishing active, critical thinking in sensitive and complex areas such as global inequalities, the structures of power and poverty, and social justice, may seem a daunting proposition for teachers but we (and others) are here to help. There are a whole range of brilliant resources and much support for schools to build these strong foundations of understanding before embarking on a school partnership.

We especially recommend our forthcoming critical learning resources and lesson plans in the following areas (each of these can be delivered by schools themselves or, in many cases, the SMP can arrange a Malawian speaker to deliver the work in person or digitally):

- Power and poverty, a critical understanding

- Use of images and video: the narratives we construct

- Scotland and Malawi: Understanding our shared history

- Partnership vs charity

- Critical dialogue groups (with QMU and StekaSkills)

- Understanding the ‘White Savior’ complex

- Do No Harm: exploring intended and unintended consequences

- The case for Climate Justice

- Understanding Malawi: its language and culture

We also really recommend that schools use the brilliant “Radi-Aid: Africa for Norway” satirical videos, produced by the Norwegian Students’ and Academics’ Assistance Fund (SAIH), as a way of supporting learners to reflect on stereotypes and oversimplifications. These videos include:

The StekaSkills/QMU report ‘An alternative to voluntourism: how Youth Solidarity Groups in Malawi empower young Malawians and Scots’ paints a powerful picture of how, when you scratch below the surface, some interactions between young Scots and young Malawians can do real damage if not carefully structured. The report includes testimony from young Malawians who had been involved in well-meaning but ill thought through visits, which at times left the Malawians feeling disempowered and disrespected:

“ ”StekaSkills/QMU report.“They would bring gifts which they would distribute themselves to who they liked the best and the rest of us didn’t benefit. And often these gifts were things we didn’t need.

They didn’t talk to the older ones who are the same age as them, they just gave toys to the youngest children and took pictures and put them up on Facebook without asking.

I hated their attitudes towards us. I hated them for that. We tried to tell them what to do and not do, but they didn’t listen and just did what they liked.”

The report sets out a technique which groups can use as young Scots and young Malawians meet -Youth Solidarity Dialogue Groups – which ensure power imbalances are addressed by giving ownership and agency to the Malawian participants.

The Youth Solidarity Dialogue Model is specifically designed for young people and works by taking them through stages of building awareness and agency so that they are motivated to try and bring about social change in solidarity with their allies. The first stage is about helping them be critical about circumstances they often accept as ‘normal’ so don’t challenge; the second stage is about becoming brave enough to voice their real opinions with other young people who are very different from themselves; and the third stage is where they have built relationships, see each other as human beings instead of stereotypes and have enough knowledge and motivation to want to bring about change.

The report gives inspiring case studies and helpful, practical advice. We really recommend all those involved in in-person visits between partner schools, or live digital engagements, read the report and the consider adopting the approach. The SMP can offer support, training and advice.

There are lots of cultural differences between Scotland and Malawi but, transcending all of these, is a shared humanity which unites us. Unless directly proven otherwise, it’s always safest to assume that those at the other side of the partnership will have the same emotional response as you, if placed in the same situation.

So keep asking yourself this question, ‘how would I feel if it were me’, and look to really understand the lives of your partners, their day-to-day challenges, priorities and motivations, as mutual understanding and empathy are the best ways of building a strong foundation for your partnership.

There are lots of cultural differences between Scotland and Malawi but, transcending all of these, is a shared humanity which unites us. Unless directly proven otherwise, it’s always safest to assume that those at the other side of the partnership will have the same emotional response as you, if placed in the same situation.

So keep asking yourself this question, ‘how would I feel if it were me’, and look to really understand the lives of your partners, their day-to-day challenges, priorities and motivations, as mutual understanding and empathy are the best ways of building a strong foundation for your partnership.

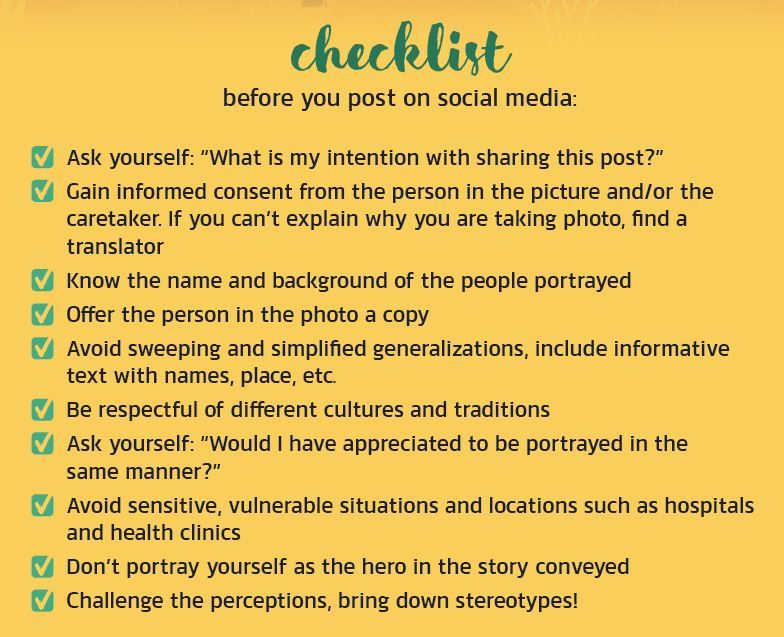

We really recommend that school members use the excellent “Radi-Aid: Africa for Norway” social media guide, produced by the Norwegian Students’ and Academics’ Assistance Fund (SAIH).

Watch their video on social media use

Read their “How to Communicate the World” Guide

SAIH have four core principles for social media use:

- Promote Dignity

- Gain informed consent

- Question your intentions

- Use your chance – bring down stereotypes

In our ‘do no harm’ section, above, we’ve explored some of the risks that could cause youth and school partnerships to inadvertently do real damage, despite the best of intentions. In this section we look to identify some of the common stumbling blocks that school partnerships can come up against and how to try to avoid these.

We recognise that, if we aren’t careful, sometimes the benefits of partnership can be hard to realise and we may even inadvertently undermine what we set out to do.

Equal partnerships sound easy on paper but in fact it can be a challenge when we live in such an unequal world.

The ‘School Partnership and school visits in a Global Citizenship Context’ report flags that, “there is a risk of reinforcing paternalism and dependency, and pity rather than empathy for the partner country”.

Here are some of the risks and issues that partnerships can come up against:

- Disempowering people, by promoting pity for a poorer country

- A focus on charity or aid

- Creating dependence

- Instilling attitudes of ‘feeling bad about our privilege’

- Using ‘othering’ language, of “them” and “us”

- A belief that Scotland has more to give than Malawi

- Cultivating attitudes of superiority or inferiority

- Too heavy a focus on difference

- The reinforcement of harmful stereotypes

- Avoiding issues of global injustice

- Being unwilling to have uncomfortable conversations

Penicuik High School partnered with Namadzi CDSS reflect,

“ ”Penicuik High School.“Having already built a relationship, and also fallen into some of the partnership pitfalls together, we were both keen to look again at how our partnership would operate, and worked to develop our first Partnership Agreement."

Ryan, SMP Youth Committee Member said,

“ ”Ryan, SMP Youth Committee Member.“I discovered that in terms of money we really had to think about the effects on the community in Malawi – putting money onto one area can cause jealousy and even violence.

You have to take a stance on the difference between giving gifts, and being asked for things that people really need. Build an understanding between each other.

Don’t reinforce a stereotype of yourself.

Make sure that you understand your partners well enough so that anything you exchange will be useful for each other.”

19 guidance points on how to avoid common pitfalls

- Make sure you really understand each other’s expectations before starting the partnership – specifically whether it is an educational link or whether you will work together on specific projects, and frame your partnership around these

- Recognise and respecting cultural differences

- Identify what you have in common and build a sense of solidarity

- Invest in relationships, really taking time to listen, understand and build friendships

- Don’t presume one side has the answers for the other

- Create regular spaces for open discussion and encourage honest feedback

- Recognise power imbalances and work pro-actively to address this

- Have a strong partnership agreement, written together and regularly reviewed

- Have a space for each side to separately share reflections on the extent to which you are living up to your principles, and share the results

- Ask open questions rather than leading questions (for example “what do you think we should do?”, not “would it be useful if we…”)

- Perhaps split the time in meetings, with each side of the partnership having half the time, to include what they want how they want

- Explore using the Critical Dialogue model

- Recognise the risk that one side might be saying what they think the other wants to hear and may be avoiding more honest answers for fear of causing upset or jeopardising the partnership. Combat this by really encouraging and welcoming honesty

- Try to ensure that decisions are jointly made and activities are jointly managed

- Ensure there is transparency and accountability between the partners

- Try to make all opportunities reciprocal

- Explore different types of wealth – not everything is about power and money

- Think critically about your own culture, assumptions and approach

- Create an appropriate space that is not only accessible, but easy for all to air grievances

We really believe that youth and school partnerships should be about two-way educational outcomes and global citizenship, rather than mini-development projects. There are a great many risks when youth and school partnerships become too focused on fundraising, charity and projects, not least the risk that a narrative of pity and poverty, or donors and dependence, can undermine a dignified partnership.

The Irma Arts (2020) report highlights that:

“ ”Irma Arts.“Activities such as fundraising and pupil visits might be more prone to reinforcing stereotypes as they often (unconsciously) reinforce images and narratives of ‘development-as-modernisation’ and the western active agent, helping the poor, passive developing country.”

If we believe listening is key to partnership, how should we react when our partners tell us they need help? Is there a risk that teaching global citizenship by highlighting extreme inequalities but then insisting that nothing should be done to challenge and change this very inequality, actually encourages a state of acceptance rather than activism? We recognise these are credible arguments and there is no right answer in this space.

We strongly recommend that youth and school partnerships are, first and foremost, built as a two-way education link rather than a development initiative.

However, we recognise that there is a gross inequality between Scotland and Malawi, in terms of wealth, power and privilege: we believe extreme poverty is the great moral outrage of our time. We recognise that it can be easy to say that school partnerships should be about education and not development, but hard to reconcile this with the principles we hold dear.

MaSP’s visit to 17 school partnerships in Malawi in January 2022 revealed that, “it is important for Scottish schools to share their mutual benefits to signify that partnership are not just about donations”.

The crucial thing, from our perspective, is that every effort is made to ensure that negative stereotypes are not reinforced and that all activity is contextualised as being part of the overall educational experience.

Beath High School partnered with Mapanga and Njale Primary Schools, add,

“ ”Beath High School.“There will always be a perception of the “haves” and “have nots” but a partnership is much more than this. Education is a very powerful tool for the future.”

Pity

Most importantly, as with all Scotland-Malawi interactions, it must be about two-way partnership driven by solidarity, not one-way charity driven by pity. The Partnership Principles are, therefore, key. Both sides of the partnership should contribute to the activism and, ideally, both should benefit (albeit likely in different ways) from the partnership.

Our advice

- Start as an educational partnership

- Make sure this is the core of what the relationship is about

- Invest in the early dialogue: a strong partnership agreement and a critical understanding of related issues around poverty and power

Irma Arts (2020) says:

“ ”Irma Arts Report.“Most partnerships and visits will include fundraising activities. The literature and partnership guide reviewed suggests to avoid fundraising, however…fundraising can play an important role in supporting partner schools and improve their ability to teach and help pupils.”

We still want to fundraise, how could we do it better?

Your partnership could have both schools or groups involved in fundraising for activities being done together including travel. It is likely that one will raise more than the other, but the main thing is that the project is joint. Do speak with your partners in all cases to see if a fundraising activity is appropriate at all for their local community in either country.

There is a difference between fundraising to provide general aid for a partner school and fundraising to support the partnership itself. For instance, people from both schools can raise funds to cover partnership expenses.

Amy Blake, CEO of Classrooms for Malawi shares,

“ ”Amy Blake, CEO of Classrooms for Malawi.“Partnerships should be reciprocal and not purely focused on fundraising. Partnerships should be drawn up in collaboration between the two schools and both schools should contribute to the outcomes and outputs. Fundraising can impact on the equity of a partnership, it is important that fundraising campaigns are positive and inclusive”

If you are fundraising, we really recommend you engage the young people in reflections around the language and images you use as part of this. The ‘Radi-Aid: Africa for Norway’ website, by the Norwegian Students' and Academics' Assistance Fund (SAIH) is a brilliant resource for this. They have a host of, funny parody videos exploring themes around negative stereotypes which can be used in lessons with young people, including their ‘Golden/Rusty Radiator Awards’. They also clearly outline what they see as the best way to communicate in a fundraising campaign in ways which are nuanced, creative and engaging, without using stereotypes.

Assess each other’s capacity

In cases where money is involved, schools and youth groups need to assess each other’s capacity and ability to manage resources.

There needs to be very careful discussion and clear agreement about the processes that will be followed.

We have seen a number of school partnerships fall apart once money has become involved as trust breaks down and suspicions within the local community arise.

Amy Blake, CEO of Classrooms for Malawi mentions,

Case Study: David Hope-Jones, SMP Chief Executive shares:

I remember that during a visit to Malawi a number of years ago I was asked by our sister network to visit a very rural Malawian school where trust had broken down surrounding how funds were used in a school partnership. I was deeply uncomfortable having any perceived ‘policing’ role but agreed to visit the village and speak to those involved. We spent a full day speaking with the different stakeholders, including:

- the Malawian teacher who was the driving force behind the partnership and who had received funds from their partner school in Scotland

- the Malawian headteacher who was suspicious and jealous of the teacher, as he had not been more directly involved in the work

- the local Priest, who again was suspicious and critical, feeling he should have been involved.

My honest belief, looking at all that had been purchased for the school with the funds transferred, was that there was no misappropriation of funds but there was undoubtedly insufficient accountability and transparency. The teacher had received funds to his personal account, receipts were kept (but in a box at his home), and there was no real record keeping. I believe this was simply because the individual involved did not have experience of record keeping, project management or the norms of basic good governance. As a result, key relationships in this small community broke down, trust was lost and real damage was done. We advised that the pre-existing school and community committee took over management of the project, with the lead teacher remaining a key part of things within this committee structure, so all the key local stakeholders could see the accounts and there was collective oversight and responsibility.

I always remember this village when we advise Scottish schools. I encourage school partnerships to resist the (understandable) temptation to fundraise and send funds but, if they do go down this road, to really invest time in ensuring Malawian partners have appropriate governance structures in place. Without them, you can be putting your friends and partners in Malawi in hugely uncomfortable and unfair positions, and you can be doing real harm to social cohesion in small communities. 5,000 miles away, it’s almost impossible to really understand the communities you are working with, so it’s always best to use existing structures and committees where you can.

MaSP’s January 2022 visit of 17 Malawian schools with Scottish partnerships identified many excellent links and considerable positive impacts on the ground in Malawi. However, it also identified some of the issues that can arise when school partnerships start involving money. There have been instances of Malawian schools lacking appropriate governance structures and safeguards to ensure due accountability. It can be difficult to ask a partner about such systems, without feeling you are risking causing offence, but it is essential that both sides have strong understanding of, and confidence in, governance structures before any fundraising begins

Amy Blake, CEO of Classrooms for Malawi mentions,

“ ”Amy Blake, CEO of Classrooms for Malawi.“If schools do choose to travel and are fundraising for a trip it is important to be transparent about the total cost of the trip and what % of donations will go toward covering travel costs and what % will go toward activities at the partner school in Malawi.”

It is essential to have funds kept in a recognised group bank account, with all processes clearly agreed, and with the appropriate school/community committees structures used.

The SMP and MaSP are able to give advice and support to school partnership which need to handle funds.

Irma Arts (2020) notes,

“ ”Irma Arts.“[Whilst] many teachers are aware of the imbalance that can exist between partner schools and do reflect on the equity of their partnership, some were struggling in how to best address these questions.”

Discussion questions for working group, if considering raising funds:

- How does charitable fundraising affect the equality of the relationship between our partner schools?

- How can your school partnership best manage the tensions between expectations of financial aid and educational aims?

- Does money equal quality work?

- How might raising funds for the partnership affect its wider communities?

Money can easily distort equal partnership and perpetuate longstanding issues of aid, dependency, and power – the very things partnerships exist to try eliminate. It is essential to set out clear expectations in your partnership agreement and regularly revisit this.

Quotes:

“ ”The Malawi Scotland Partnership.MaSP comments: “It is okay for schools give each other money, however this is not the sole activity in the partnership. Transparency and accountability is highly encouraged to not interfere with the school partnership… It’s complex, but both schools need to understand all money is raised through funding raising or lengthy applications.”

“ ”Caroline Beaton, Teacher.Teacher Caroline Beaton urges: “funding needs to be less of a focus to make partnership sustainable”

“ ”Ian Mitchell, Teacher.Ian Mitchell of Beath High School believes: “Partnerships based on trust will continue”

“ ”Max, SMP Youth Committee.Max, SMP Youth Committee, shared: “Our school had policy of declining gift requests. If anything was to be given, it was agreed with teachers. “

“ ”Ryan, SMP Youth Committee.Ryan, SMP Youth Committee found in his experience: “In terms of money giving, think about the effects on the wider community in Malawi – it can cause jealousy and even violence.”

“ ”Max, SMP Youth Committee.Max, SMP Youth Committee, mentions that: “People got tired of fundraising where I live, in small Highland community.”

“ ”Some points of view from our SMP and MaSP Youth & Schools Forum 2021:

“receiving for free doesn’t work for sustainability”

“fund just a phone for Whatsapp for example”

“funding needs to be an open conversation in your partnership agreement”

Other different opinions on fundraising from members in a recent Forum meeting:

“Some fundraising will be required no matter what the principles.”

“funding should not be the primary activity”

“there is more benefit in exchanging ideas or challenges”

“focus should be on capacity building for both teachers from both sides”

“Funding is the most important thing! But needs a sustainability plan”

“Don’t think of it as fundraising, make it more intertwined with building bonds and strengthening. Eg. Into an event, create different teams, Malawians can also learn from experience of fundraising.”

“Do sustainable projects like a social enterprise or exchange recipe books to make and sell”

“People donating need to be actively involved in something that connects them to Malawi/Scotland”

“I sold chickens eggs and raised £1000 for my partnership! It could have been something both sides of the partnership could do. Why not choose a fundraising activity both sides can get involved in and have fun?”