Understanding the ‘White Saviour’ complex and ‘volun-tourism’

This session supports a critical understanding of ‘white saviour’ behaviours, which see white people depicted as liberating, rescuing or ‘saving’ Black and People of Colour (BPoc) communities. It identifies key aspects of ‘white saviourism’, highlights how damaging and dangerous they can be, and gives practical advice on how to avoid ‘white saviourism’ in international working. It also explores the pros and cons of ‘volun-tourism’, through the critical lens of ‘white saviourism’, and discusses how learners can themselves challenge ‘white saviourism’.

| Key learning outcomes | Learning intention |

|---|---|

| Understanding what is meant by ‘white saviour’ and can identify these behaviours | I know what ‘white saviour’ means |

| Understanding of the seen and unseen damage that ‘white saviourism’ can do | I see how ‘white saviourism’ does real damage |

| Appreciation of the complexity and sensitivity of such issues, and the dangers of making assumptions about others with limited knowledge | I see that this is complicated – that nothing is 100% ‘good’ or 100% ‘bad’ and you need to really listen to people to understand |

| Understanding the risks that ‘volun-tourism’ can be ‘white saviourism’ but also an appreciation that not all international work is bad | Travel and volunteering in countries like Malawi can be good if done well, but I can see how it can also do harm if not |

| Understanding tools and ways of thinking which will help learners avoid ‘white saviourism’ when working internationally | I know how to try and avoid becoming a ‘white saviour’ |

| Ability to discuss this complex topic constructively and appreciation of the importance of self-reflection and modifying your own action before criticising others | I can see the sensitivities here and why it’s more important to change my own actions rather than try to make myself look good by criticising others |

Teacher notes: Introduction to this session:

This webpage gives all you need to deliver a lesson exploring ‘white saviourism’ and ‘volun-tourism’. This is a hugely important area but we recognise it is complex, sensitive and important to get right. As presented here, it is most suitable for upper-secondary but many aspects of this lesson could be adapted for different age and stages.

The lesson is made of five units. You don’t have to do all five. We have put three key learning outcomes in a text box at the end of each section, so you can pick and choose.

Most of the units are framed around class discussions. There is also a short online video to trigger discussion. There is also an accompanying PowerPoint presentation, with notes, which you can use to deliver this lesson.

We’re here to help, so if you want any support, advice or even someone to come and deliver this lesson for you, please just email youth@scotland-malawipartnership.org.

Do No Harm:

In keeping with our Partnership Principle, ‘do no harm’, we encourage teachers in delivering this lesson to be careful they do not unintentionally:

- Reinforce negative stereotypes about the global south.

- Leave learners with a sense that all interaction between the global north and the global south are inherently questionable – this is not the case.

- Leave learners scared to engage internationally for fear of being called out or getting the language wrong – it is important to speak of the benefits of internationalism and global citizenship.

- Deny that extreme poverty exists in countries like Malawi, that there is significant social injustice in the inequality between countries like Scotland and Malawi, and that there is crucial value in working together with countries like Malawi to call this out and look to reduce these inequalities

- Encourage unnecessarily hostile, combative or polemic attitudes towards others, even those which might be guilty of elements of a ‘white saviour’ behaviours. Rather, look to build a depth of critical understanding, showing the complexity and encouraging learners to think of ways to challenge and change which are constructive and empathetic (discussing not shouting!).

SECTION ONE: What is a ‘White Saviour’

Ask learners this question, listen to their level of existing knowledge and facilitate a discussion.

Q – What is a ‘White Saviour’

A ‘white saviour’ is a critical term that is used to describe a white person who sets out to help, or ‘save’ a non-white person, very often in the developing world. Their actions are often driven by negative assumptions: that they know best what is needed and how to help, and that local communities do not have the skills to help themselves. While seemingly well meaning, such actions are often driven by a motivation to make themselves look or feel good.

Often ‘white saviours’ parachute into a local community, looking to ‘do good’ but not listening to those in the community or acting in a respectful manner. In the stories that white saviours tell, through words, pictures videos and on social media, they are themselves the ‘heroes’ and local communities are seen as ‘helpless recipients.

Since 2018, there have been an increasing number of voices looking to ‘call out’ white saviourism in different places, most notably criticising certain celebrities and charities.

Four key questions when considering ‘white saviourism’ are:

- What are the motivations?

- What are the assumptions?

- Who is the ‘hero’ of this story?

- What is the impact (positive and negative; seen and unseen; intended and unintended)?

This is what we will explore in this lesson.

Watch ‘How to Get More Likes On Social Media’ produced by Norwegian Students' and Academics' Assistance Fund (SAIH). [1.27]

Facilitate a class discussion around the below questions, looking to draw out the following points.

Q - What was her motivation for going to Africa?:

- To increase her own popularity and profile on social media.

Q - What assumptions might she have had about Africa and what it would be like?

- It is very poor and there are many people in desperate need.

- She will be automatically welcomed by local groups.

- She will ‘do good’ just by going there.

- It will make her look good to do so.

Q – Who is she setting up to be the ‘hero’ of this story on social media?

- Herself

Q – What impact is this having (seen and unseen, intended and unintended)?

- Disrespecting those she visits and taking away their dignity.

- Getting in the way of the local teacher and teaching culturally inappropriate topics.

- Getting in the way of local medical staff trying to do their jobs.

- Sharing negative stereotypes about Africa on social media (this narrative only makes it harder for parts of Africa to build their own economies and encourage others to invest – countries can become defined by poverty and this does real damage).

- Encouraging others to do the same as her.

- Contributing to climate change through long-haul travel.

Q - Is it always wrong to go to Africa and try to help? Are development projects involving people in the global north and the global north working together always bad? Is this always ‘White Saviourism’?

No [Listen to learner’s views and use this to lead into the next section].

- ‘White saviourism’ is about assuming that you have the solutions that other communities need: it makes you the hero and others seem helpless and grateful.

- Social media, and the desire to look and feel good, drives ‘white saviourism’.

- ‘White saviourism’ does real harm: it robs people of their dignity.

SECTION TWO: How to avoid being a ‘White Saviour’

Ask the class the below question and facilitate a discussion, looking to draw out the following points.

Q – How could the lady in the video have engaged Africa in a way less likely to be ‘white saviourism’?

Use the below headers to prompt learners’ thinking in the discussion. Click each header for points to try and draw out of discussions.

Motivation

She could think carefully about what is motivating her and ensure it is not about her own self advancement or others perceptions of her. She would probably then make different decisions.

Assumptions

She could think carefully about what assumptions she has before travelling. Then look to build her own understanding to challenge these assumptions. Perhaps by joining communities working with that country and listening to others, as well as reading literature and consuming media produced by people in that country.

Hero

She could ensure the story she is presenting to others does not have herself as the hero – instead focusing on what the local teacher and the local doctors and nurses are achieving.

Partnership

Ideally, she could establish links directly with an individual or group in that country, such that she can really listen to their experience of life, looking to understand what their needs and priorities are. Through two-way dialogue she could use this as an opportunity to share about herself as well, being honest about the challenges, issues and shortcomings she faces, with humility and self-awareness. In this way, she would build solidarity and mutual understanding in a respectful way.

Travel

Most importantly, she could unpack and challenge the assumption that travel to a country like Malawi will automatically help Malawians: why would it help? She could think about the risks of travel: the climate impact, the risk she reinforces stereotypes, and the risk she might make others’ lives worse. She could explore alternatives to travel: perhaps supporting a locally-run charity if her motivation is to ‘do good’. If a genuinely dignified, two-way partnership is built up, with self-awareness and mutual understanding at both sides, it is absolutely possible to travel to countries like Malawi in ways that genuinely help both sides.

Reciprocity

The best way to build empathy and mutual understanding is the simple thought experiment: ‘how would I feel if it were the other way around?’. In this case, how would she feel if someone from a richer country came to her community, didn’t talk to her but took photos for social media which made her look bad, and then assumed they had ‘saved her’. If you can keep asking yourself ‘how would I feel if this were the other way around’ and you’re comfortable with it, you’re probably more likely to be on the right track.

Representation

If you are taking images or using social media, think seriously about how you are representing those you meet. The Norwegian Students' and Academics' Assistance Fund (SAIH), who made this video, have four key principles with regards how to use social media:

PRINCIPLE 1: PROMOTE DIGNITY

Promoting dignity is often ignored once you set foot in another country, particularly developing countries. This often comes from sweeping generalizations of entire people groups, cultures, and countries. Avoid using words that demoralize or further propagate stereotypes. You have the responsibility and power to make sure that what you write and post does not deprive the dignity of the people you interact with. Always keep in mind that people are not tourist attractions. Learn more

PRINCIPLE 2: GAIN INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent is a key element in responsible portrayal of others on social media. Respect other people’s privacy and ask for permission if you want to take photos and share them on social media or elsewhere. Avoid taking pictures of people in vulnerable or degrading positions, including hospitals and other health care facilities. Specific care is needed when taking and sharing photographs of and with children, involving the consent of their parents, caretakers or guardians, while also listening to and respecting the child’s voice and right to be heard. Learn more

PRINCIPLE 3: QUESTION YOUR INTENTIONS

Why do you travel and volunteer? Is it for yourself or do you really want to make a difference? Your intentions might affect how you present your experiences and surroundings on social media, for instance by representing the context you are in as more “exotic” and foreign than it might be. Ask yourself why you are sharing what you are sharing. Are you the most relevant person in this setting? Good intentions, such as raising awareness of the issues you are seeing, or raising funds for the organization you are volunteering with, is no excuse to disregard people’s privacy or dignity. Learn more

PRINCIPLE 4: USE YOUR CHANCE - BRING DOWN STEREOTYPES

When you travel you have two choices: 1. Tell your friends and family a stereotypical story, confirming their assumptions instead of challenging them. 2. Give them nuanced information, talk about complexities, or tell something different than the one-sided story about poverty and pity. Use your chance to tell your friends and stalkers on social media the stories that are yet to be told. Portray people in ways that can enhance the feeling of solidarity and connection. A good way forward is to ask the local experts what kind of stories from their life, hometown, or country they would like to share with the world. Learn more

- To avoid white saviourism, it’s valuable to reflection on: what are your motivations, what are your assumptions, who is the ‘hero’ of your story, and what are the impacts of your actions?

- When you think this way, you realise sometimes travel is not the best way to achieve what you want (but this doesn’t mean all travel is bad).

- There’s a really useful thought experiment to test your actions against: how would I feel if this were the other way around?

SECTION THREE: Identifying ‘White Saviourism’

Go through each of the three case studies below, facilitating a short discussion as a class or in groups, after each. You could ask learners to stand in a continuum line: standing against one wall if they think this is 100% White Saviourism, the opposite wall if they think 100% not White Saviourism, or somewhere in between if they think partly.

Case Study 1:

A Scottish school goes to Malawi and paints a library of the school. The is no existing partnership with the school before the visit and one does not develop from the visit. There is very little contact or discussion between the young Scots and young Malawians, apart from a brief event as they arrive and when they leave. The young Scots tell their stories on video and social media. Is this ‘White Saviourism’?

Discussion points to try and bring out:

- Yes. There certainly seems to be some uncomfortable aspects here which might be described as having elements of ‘white saviourism’

- Why are they painting the library, could this not be done more cheaply and better by Malawians? Who identified this as a priority?

- Are there educational benefits if the Scots and Malawians aren’t speaking to each other?

- What story are the young Scots telling on social media if they haven’t really spoken to the Malawian young people? Are the Malawians able to tell their story?

- Is this just reinforcing stereotypes?

- Is there an unequal power relationship?

- BUT, to really unpack any further, or have any depth of understanding, you would need far more information. Most importantly, you would have to really listen to both sides.

Case Study 2:

A Scottish and Malawian school have a longstanding partnership together in which there is regular communication by WhatsApp and email, between teachers and students. There are occasional reciprocal visits (both Scottish teachers and students going to Malawi and Malawian teachers and students going to Scotland) but there is also regular educational work together between visits, including live links for discussion between classrooms. Both sides contribute and both sides benefit from the links together. Is this ‘White Saviourism’?

Discussion points to try and bring out:

- This looks less like ‘White Saviourism’ because:

- There is a real, two-way partnership

- Both sides seem to be setting the agenda

- Both sides have the same opportunity to travel

- Both sides benefit

- It feels respectful and reciprocal

- BUT, are there still assumptions behind this work? Again, to really understand you need more detail and to really listen to those involved.

Case Study 3:

A Scottish and Malawian school have a link together and regularly exchange messages. Their Partnership Agreement includes specific school improvements in Malawi, identified by the Malawian school, for which the Scottish school fundraises and transfers money. Is this ‘White Saviourism’?

Discussion points to try and bring out:

- Elements of this are potentially uncomfortable, and some might say there is ‘white saviourism’ if there are assumptions that the Scottish side is ‘solving’ the problems of the Malawian side through the fundraising.

- But there is a partnership agreement and the needs have been identified by the Malawian side.

- To draw any real conclusions you would need far more information about the nature of the partnership, how it arose, the tone off communications, how each other is represented, etc.

- Understanding ‘White saviourism’ is complex and sensitive.

- It’s important not to jump to conclusions with limited information. You have to really listen to really understand.

- Nothing is 100% ‘good’ and nothing is 100% bad

Q - What is volun-tourism?

Voluntourism is a form of tourism in which travellers participate in voluntary work, often for a charity. Volun-tourists range in age and come from all over the world. The work they do can be related to agriculture, health care, education and many other areas. Aspects of volun-tourism have been criticised for being part of the ‘white saviour’ complex.

Q – Is volun-tourism good or bad?

Split the class in two and ask one side to think of reasons why volun-tourism might be a good thing and one side to think of why it might be a bad thing.

Arguments against voluntourism:

- Volunteers sometimes lack experience: they wouldn’t be qualified to build a school in Scotland, so why should they in Malawi?

- Work could almost always be done more cheaply using local labour – this would also support the local economy.

- Climate impact of long-haul travel.

- Local resources can be drained supporting visitors, with food, accommodation and support which takes away from local communities.

- It can reinforce negative stereotypes.

- It can build resentment between local communities and visitors.

- The real beneficiaries are often the visitors, in terms of personal development and a ‘feel good; holiday, but they are made to feel they have helped a local community.

Arguments in favour of volunteerism, if well managed

- If done in a sustainable way, a volunteer’s actions can have long-term positive impact in communities

- Both sides (host and visitors) can learn about each other’s cultures, building mutual awareness and developing friendships

- Can help stimulate local economies

- Can help increase a sense of solidarity, helping create ‘global citizens’ in both nations, who then go on to support positive international engagements

- Gives a greater appreciation of the challenges and opportunities others have, triggers self-awareness of the privileges those from richer countries enjoy, raises awareness of global economic injustice

Q - Is all Volunteering bad?

No. Many parts of life and society in Scotland are reliant on volunteers: people giving up their time without payment to help others. The same is true in Malawi. Just as its not automatically inappropriate for someone internationally to volunteer in Scotland, it’s not automatically inappropriate for someone from Scotland to volunteer elsewhere. It’s the detail that matters: how they volunteer, how they work with local communities, whether it is respectful, two-way and helpful.

Q - Is all Tourism bad?

No. Countries like Malawi reply on tourism for sustainable economic development, just as we do in Scotland. It is essential to understand the impact of your travel, on both the climate and local communities, but it’s important we don’t deter all travel to Malawi. It is a fantastically beautiful country and an amazing holiday destination. Learn more at www.visitmalawi.mw and www.malawitourism.com

Q - Is all volun-tourism bad?

Not necessarily, although it’s increasingly been used as a critical term. The important thing is measure it against the same set of four questions:

- What are the motivations

- What are the assumptions

- Who is the ‘hero’ of this story?!

- What is the impact (seen and unseen, intended and unintended)

The quickest and best test is asking yourself ‘how would I feel if this were the other way around’ test.

- Volun-tourism is a type of tourism which involves volunteering

- Not all tourism is bad, not all volunteering is bad, therefore not all volun-tourism is bad; however, it is all too easy to slip into the ‘white saviour’ complex if you think you are going somewhere to ‘do good’. This can do real harm

- It is therefore important to think about: what are your motivations, what are your assumptions, who is the ‘hero’ of your story, and what are the impacts of your actions.

Ask learners to vote with their hands which answer they agree with most to the following question:

Q - What is the best way of ending white saviourism?

- Publicly call out and criticise those you believe to be ‘white saviours’ and look to ‘cancel’ them

- Learn as much as possible about others’ work and look to have a discussion with them to raise your concerns

- Focus first on the motivations, assumptions and impact of you own words and actions.

Try to draw out the following in discussions:

Recent efforts to ‘call out and cancel’ those seen as ‘white saviours’ has helped expand the debate, raise awareness and has encouraged many more people and organisations to think seriously about their motivations, assumptions and impact.

However, this is a complex area and it is risky to try and judge others with limited information: it’s ultimately the communities on the ground who are best placed to say what is harmful and what is beneficial. It is these communities we should be listening to.

Often, even those doing the criticising online would do well to go through the same self-reflection: what are their assumptions, what are their motivations, who is the hero of their story, and what is the impact of their actions. If you are criticising others based on what you assume others are doing; if you are motivated to criticise others to make yourself look good; if you are the ‘hero’ for calling out others; and if your criticism is having a really harmful effect on others, it is possible you are just as ‘guilty’ as those you are looking to criticise.

Constructive challenge, discussion and debate is a good thing but simply shouting at others based on your presumptions of what they are doing wrong rarely achieves much.

Far better, look to understand, engage and positively influence. And most importantly, focus on your own words and actions, examining your own motivations, assumptions and impact. This is where you have the most control, and this is how you can therefore have greatest impact.

Perhaps we should

- FIRST… ‘Focus first on the motivations, assumptions and impact of you own words and actions’

- ONLY THEN… ‘Learn as much as possible about others’ work and look to have a discussion with them to raise your concerns’

- AND ONLY THEN… ‘Publicly call out and criticise those you believe to be ‘white saviours’

Q – Is anyone willing to share a personal reflection from this lesson, perhaps a time you might -looking back- have acted with a ‘white saviour’ mindset?

Ensure this is a supportive and safe space for people to share, in which no one feels judged if they share. We recommend teachers have an example they can share, regarding their own past thoughts, words and actions.

Q – Can everyone try to think of one thing you could do differently yourself, as a result of your learning today?

- Debate and discussion are crucial ways for us to learn from each other, challenge assumptions, and explore different ways of working.

- However, it can be dangerous to make conclusions about others’ work with limited information and simply jumping with others to criticise or cancel someone, whether in social media or real life, is very rarely the best way to bring about positive change.

- You have greatest control over your own actions, not others’. So use your understanding of ‘white saviourism’ and ‘volun-tourism’ to critically examine your own motivations, assumptions, words and actions.

Power and poverty, a critical understanding

A session exploring the scale of inequality between Scotland and Malawi (the global north and the global south), some of the structural causes of poverty and the continuing relationship between poverty and power. It highlights some of the challenges of having an equitable relationship where there is a power imbalance and the difference between equity and equality. It helps learners identify continuing global injustices and power imbalances which can reinforce poverty and gives practical examples of how this can be challenged through activism. Examples include: Malawi’s role in SADC and the UN LDC group, and the injustice inherent in different delegation sizes in COP26 and other key global negotiations.

| SMP Learning Outcomes | Learning intention |

|---|---|

| Awareness of the scale of economic and social inequality between Scotland and Malawi, and the human implications of this | I can see how different life is in Scotland to Malawi and I can see the unfairness in this |

| Critical reflections about some of the causes and consequences of poverty, and understanding of why some poor countries can continue to get poorer | I can see there are lots of reasons why people are poor, which are not that person’s fault |

| Critical reflections around the relationship between power and poverty, and how this can become self-fulfilling | I can see that if you are poor, you often don’t have so much power, and if you don’t have power you’re likely to get poorer |

| Basic awareness of steps that can be taken, by individuals and governments to use power to fight for social justice | I can see what could be done, by me and others, to make a fairer system |

Credits and useful resources

Development Education - 'Poverty Explored'

Teaching English - 'Ending Poverty'

Our World in Data.org - 'Extreme Poverty'

World Bank - 'POWER, RIGHTS, AND POVERTY: CONCEPTS AND CONNECTIONS'

'Introduction: Power, Poverty and Inequality'

Oxfam - 'From Poverty to Power: How active citizens and effective states can change the world'

Teacher notes: Introduction to this session:

This webpage gives you all need to know deliver a lesson encouraging a critical understanding of the relationship between poverty and power. The learning resource is made up of three sections, each of which has three learning outcomes. You don’t have to deliver all three, feel free to pick and choose, or just focus on one of these sections.

This is a complex, important and potentially sensitive area. We have written this resource for discussion at a mid to upper secondary level but it can be amended and simplified to make it accessible for lower ages and stages.

The focus in section one is on Scotland and Malawi, as examples of a richer country in the global north and a poorer country in the global south, but the rest of the resource is not country-specific.

There is an accompanying PowerPoint which you can use to deliver this session, editing however you wish.

We’re here to help, so if you want any support, advice or even someone to come and deliver this lesson for you, please just email youth@scotland-malawipartnership.org.

Do No Harm:

In keeping with our Partnership Principle, ‘do no harm’ we encourage teachers in delivering this lesson to be careful they do not unintentionally:

- Reinforce negative stereotypes about the global south.

- Ignore the existence of poverty and inequality in Scotland.

- Leave learners with a sense of helplessness, that there is nothing they can do to fight poverty.

- Encourage ‘white saviour’ ways of thinking: that richer countries can and should set out to ‘save’ poorer countries (see our separate lesson on this topic).

Contents

Explain that you want to explore poverty and power in this lesson, using Scotland and Malawi as an example but first its important to build our understanding of the two nations.

Use the PowerPoint to explore each of the below points of comparison, for each showing learners the figure/data for Scotland and then asking learners whether they think the figure for Malawi is higher or lower.

Landmass:

- Scotland = 77,900 km2 (Wikipedia)

- Malawi = 118,480 (World Data)

- So, Malawi is 52% bigger than Scotland

Population:

- Scotland = 5.5 million (2021, ONS)

- Malawi = 20.3 million (2022, WorldoMeters)

- So, Malawi has almost four times as many people in it

Urban:

- Scotland = 83% of population is urban (2019, Scottish Government)

- Malawi = 18% of population is urban (2021, World Bank). However this is growing at 4.4% a year – this is the 8th fastest urbanisation rate in the world (World Population Review).

- So, Malawi’s population is over 4 x more rural than Scotland’s, but changing fast

Total Income per person (GNI per capita):

- Scotland = £29,629 (2020, Statista)

- Malawi = £548 (2022, MacroTrends)

- So, Scotland has 54x greater income than Malawi

Typical jobs:

- Scotland = Biggest sector is health, social work and retail – 15% (2021, Scottish Government)

- Malawi = Biggest sector is smallholder farming (mostly subsistence) - 80% (USaid)

Age:

- Scotland = Median age is 42 (2020, Statista), life expectancy is 77 (2020, Statista)

- Malawi = Median age is 18 (2020, WorldOMeter), life expectancy is 62 (2019, World Bank)

- So, your average Malawian is under half the age of your average Scot

Government healthcare budget

- Scotland = About £2,900 per person, per year (2022, Scottish Government)

- Malawi = About £10 per person, per year (2021, Unicef) [even if you add all aid spent on healthcare, it is still just £35 (2020, Unicef)]

- So, Scotland spends 290 x more on healthcare than Malawi, per person

Government education budget

- Scotland = £864 per person, per year (2022, Scottish Government)

- Malawi = About £20 per person, per year (2022, Unicef)

- So, Scotland spends 43 x more on education than Malawi, per person

University enrolment

- Scotland = 56% (2019, World Bank)

- Malawi = 1% (2018, World Bank)

- So, Scots are 50 x more likely to go to university than Malawi

So:

- your average Malawian is 18 years old, lives in a rural area, is a subsistence farmer, earning £548 a year, won’t go to university and has only £10 of healthcare a year from government

- your average Scot is 42 years old, lives in an urban area, works in health, social care or retail, earning £29,900 a year, has been to university and has £2,900 of healthcare a year from government

But, important to remember that:

- these are averages and generalisations, there is diversity and inequality in both nations: there are rich Malawians and poor Scots

- Malawi is not defined by its poverty: it is a beautiful, welcoming, fun, entrepreneurial countr

Q - What are the similarities between Scotland and Malawi?

Use the pictures on the slide to facilitate a discussion, encouraging points like the below to come out around the shared human experience

- Love of family

- Love of sports [you could mention Malawi is 7th in the world at netball, Scotland is 10th (2022, Netball.sport)]

- Human emotions: to laugh, to smile, to cry

- Want to protect children

- Wanting to earn money

- Social media and mobile phones

- There is a fundamental inequality between Malawi and Scotland, in wealth, education, healthcare and almost all aspects of life

- But Malawi is not defined by its poverty

- While there are many differences between Scotland and Malawi, there are also many similarities: we are all human and we all feel the same emotions, hopes and expectations.

Facilitate a discussion around the following questions, trying to bring out some of the below points.

Q - What are the effects of poverty (what does poverty result in)?:

- Shorter lives

- Lack of jobs

- Low education levels due to underfunded schools

- Illness and disease due to weak healthcare system

- People unable to pay taxes

- Corruption

- Lack of clean water

- Food insecurity

- Vulnerability

- Lack of power and energy

Q- What are the causes of poverty?

- Lack of education

- Lack of healthcare

- Lack of jobs

- Lack of reliable electricity and energy

- Conflict

- Climate change

- Natural disasters

- Poor infrastructure (roads, railways, etc)

- History – colonial rule

- Language

- Unfair tax and trading rules

- Lack of rights

- Lack of food and clean water

- Less efficient farming practices

- Debt

- Corruption

- Inequality

- Unequal global power [use this to lead into section three]

Q – How many of these causes are the fault of the people involved?

Almost none of these causes of poverty are the fault of individuals but rather are a set of circumstances imposed on whole communities and countries, often for generations.

Q – Do you notice anything in common between the causes and consequences of poverty?

Many things (like poor education and healthcare, weak governance, lack of power and infrastructure) are both consequences of poverty and causes of poverty. This means there can be a downward spiral – a vicious circle. For example, because you are poor you pay less tax to government, this means the government has less to spend on healthcare, so your health worsens, and you get poorer. It can be incredibly hard to break this cycle.

- Poverty is complex, it has lots of causes, but almost none relate to any failures of individuals.

- Some causes of poverty are also consequences of poverty.

- Poverty can be a vicious circle: meaning poor parts of the world can get poorer while rich areas get richer.

Facilitate a discussion around the below questions, trying to bring out the following points. You can use the PowerPoint as a way to structure the discussion.

Q - What are the different types of power countries have?

- Economic: Money and ‘purchasing power’ to influence others.

- Political: Structures and systems which mean some countries have more of a say on how things are run and what the rule are.

- Social: The education and health of the nation, and social networks.

- Environmental: The ability to affect climate change and how vulnerable you are to a changing climate.

- Military: The size and budget of the armed forces.

- Cultural: The language you have, TV programmes and films, ‘soft power’.

- Historical: The previous power you had over other nations (empire, colonies, etc) and the relationships this has left.

- Natural Resources & produce: Oil, gas, minerals, etc

How much of each of these types of power do Scotland and Malawi have?

| Power | Scotland | Malawi |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | HIGH. Scotland is much richer and can buy goods and services, and use its money to influence others | LOW: Malawi is much poorer and is less able to buy goods and services, and use money to influence others |

| Political | HIGH: Scotland is a part of key groups of rich countries like the G8, Nato, UN Security Council, etc, and so has greater global influence (although perhaps less now not in the EU) | LOW: While a part of the Commonwealth, Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) and the African Union (AU), Malawi still has comparably little global influence. |

| Social | HIGH: Scotland has comparably high levels of education and health, and strong social networks. | LOW: Malawi has comparably low levels of education and health, and strong social networks. |

| Environmental | HIGH: Scotland can move to renewable power and is able to invest in protections against a changing climate | LOW: Malawi is less able to invest in renewable energy and is much more vulnerable to a changing climate (crops will fail which are needed to feed the growers’ own family) |

| Military | HIGH: Scotland has a significant military capabilities | LOW: Malawi has much smaller armed forces |

| Cultural | HIGH: English is spoken around the world and Scottish / UK cultural exports are consumed across the globe | LOW: Malawi’s official language is not its own and its own culture has little global influence |

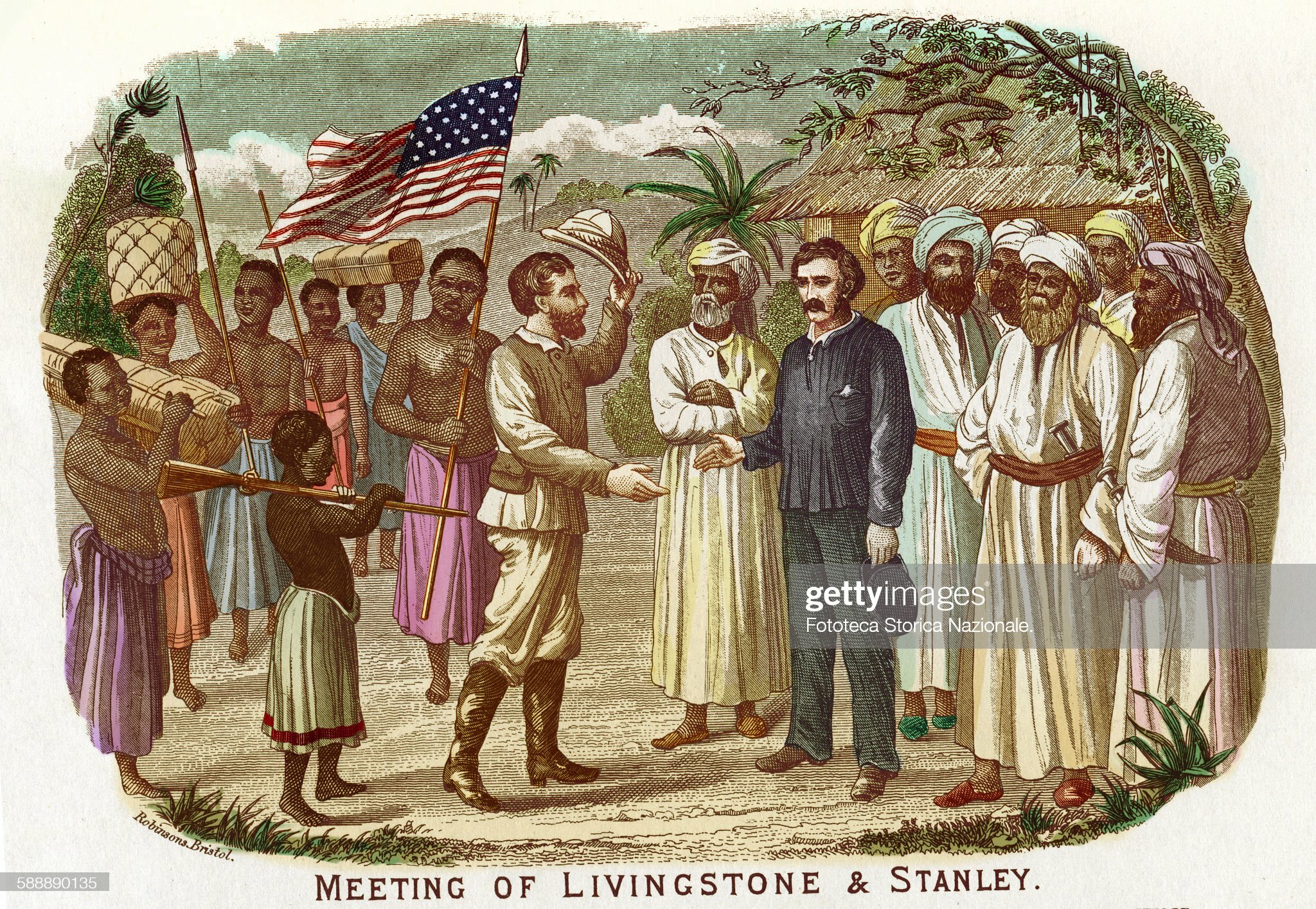

| Historical | HIGH: Scotland, as part of the UK, had an empire across the world and many of these unfair and unequal power relationships remain | LOW: Malawi was a British Protectorate called ‘Nyasaland’ and, from 1953-63 a part of the racist British Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Many of Malawi’s laws and institutions come from this period. |

| Natural resources & produce | MEDIUM: Scotland has limited remaining oil and gas in the north sea, but relatively few other natural resources | HIGH*: Malawi has many everyday commodities consumed across the world (tea, sugar, coffee, chocolate, rice, etc) as well as high-value rare earth minerals |

Q - In only one area does Malawi have more power than Scotland. Does Malawi significantly benefit from this?

No - In reality, Malawi and other developing nations, often do not have the sort of power you would expect them to have due to their natural resources. This is because richer nations use their many other types of power (economic, historic, political, cultural etc) to ensure they can get these natural resources without having to pay significant sums. For example:

- Conflict, weak governance and unfair trading means high value rare earth materials, which are required in every smart phone, and some of which can only be found in one or two countries, are taken from some of the poorest countries with very few people benefitting in those countries despite rich countries being entirely reliant on these minerals.

- Richer countries are able to avoid paying tax in poorer countries because they have greater political power to make the rules.

- Trade rules mean that it’s incredibly hard for Malawi to export roasted, processed and packaged coffee. This means they have to export the unprocessed green beans into the EU and countries in the EU then do the processing and packaging, turning it from a very cheap commodity, to a valuable product (despite not actually growing any of it).

CASE STUDY

Did you know, if you buy a £3 (non-Fair Trade) Malawian coffee from a café:

- £1.80 (60%) goes on rent and staffing in the café

- 75p (25%) is profit and tax

- 21p (7%) goes on the cup, lid and napkin

- 12p (4%) pays for the milk

- 12p (4%) pays for the coffee

- BUT only 1p (0.4%) actually goes to the farmers in Malawi

So, of your £3, £2.99 goes to Scotland and 1p goes to Malawi, despite Scotland not being able to grow coffee! (2019, Financial Times/UN)

Q - Can you see power?

Some forms of power are quite visible – for example, wealth can buy big houses and nice cars. Other types of power are less easy to see, like cultural or historical power. Often power becomes invisible because it becomes normalised, accepted and unquestioned: rich countries can have an unquestioned and often invisible sense of power because of their history, language, culture, etc. This is why it’s so important to think and talk about power.

Q - How can richer countries use their power to help poorer countries?

- Invest in international development / aid to help address the causes of poverty, for example supporting healthcare, education, clean water, food security, etc

- Use their political power to ensure poorer countries are listened to and their interests acted upon.

- Buy goods from poorer countries, especially fairly traded goods.

- Understand the negative impact and lasting legacy of colonial rule

- Establish dignified partnerships of human solidarity – including school partnerships – to learn more about each other and work together to fight poverty

Q - How do richer countries use their power against poorer countries?

- Continuing to contribute to the climate crisis, which the poorest countries are most vulnerable to the impacts of

- Charging unfair interest on debt with developing countries

- Continuing unfair global trading rules

- Not paying fair levels of tax in developing countries

- Continuing negative stereotypes about developing countries which make it harder for poorer countries to attract trade, investment and tourism

- Undermining local government institutions by making all the key decisions

- Looking to use aid to help benefit themselves (politically, financially and through security)

- Continuing the historical colonial legacy

Q - What power do YOU have, and how do you use it for good?

- Economic – Buy Fair Trade items which see profits return to poorer producer nations

- Political – Vote for political parties committed to global economic justice

- Social – Use your social networks to share information about social and economic injustice

- Environmental – reduce your carbon footprint

- Cultural – Ensure you are not continuing harmful negative stereotypes

- Historical – learn about the UK’s colonial history and work to ensure we are not continuing colonial mindsets and power imbalances

- There are many different types of power which nations have, some are seen and some are unseen because they have become normalised over such a long time.

- Rich countries can use their power to help poorer countries (for example through aid) but this good can very easily be undone through less visible use of power which keeps poor countries poor, like unfair trading rules.

- Even individuals in richer countries have power and privileges which those in poorer countries do not, these can be used both good and bad

The power of images and video: the narratives we construct

A session exploring what images learners have of “Africa” and “Malawi” in their heads and where these images came from. Are they accurate? Are they fair? Are they helpful? The session supports empathy, encouraging learners to think about different perceptions of people in Scotland and how these make us feel. It explores the challenge for the media, charities and activists of wanting to accurately reflect the human implications and social injustice of extreme poverty in Malawi, while not reinforcing negative stereotypes or continuing a narrative of pity which undermines Malawi’s long-term economic development. The session works to dispel harmful stereotypes, showing Malawi in a positive and progressive light, highlighting the many successful Malawi-led development initiatives, encouraging empathy and critical reflection of the language and images which learners use and consume regarding Africa.

| SMP Learning Outcome | Learning intention |

|---|---|

| Negative stereotypes about Africa identified and challenged, with critical reflection about the media ‘consumed’. | I can see that some of what I previously thought I knew about Africa is wrong and harmful. |

| An empathetic understanding of the harm negative stereotypes have. | I can imagine what it would feel like if someone were to say or think these things about me. |

| Critical reflections around the different narratives, images and video used by charities; specifically, the dangers of a ‘pity narrative’, and the alternatives to it. | I can see how negative charity campaigns can do real damage, even if they raise lots of money, and there are better ways of telling stories. |

| Understanding of what learners can themselves do to question the narratives they consume, look for different sources, and avoid themselves sharing negative stereotypes on social media. | I can see what I can do to avoid negative stereotypes and harmful narratives. |

Teacher notes: Introduction to this session

This webpage gives you all need to know deliver a lesson encouraging critical thinking around the images and narratives young people consume about the developing world. The learning resource is made up of three sections, each of which has three learning outcomes. You don’t have to deliver all three, feel free to pick and choose, or just focus on one of these sections.

This is a complex, important and potentially sensitive area. We have written this resource for discussion at a mid to upper secondary level but it can be amended and simplified to make it accessible for lower ages and stages.

We talk about ‘Africa’ through this lesson but be careful to emphasise that Africa is a continent not a country.

Depending on the age of the learners, you may need to first define terms such as “stereotypes”, “narratives”, “empathy” “parody”.

There is an accompanying PowerPoint which you can use to deliver this session, editing however you wish, it has notes from this webpage embedded in it.

We’re here to help, so if you want any support, advice or even someone to come and deliver this lesson for you, please just email youth@scotland-malawipartnership.org.

Do No Harm:

In keeping with our Partnership Principle, ‘do no harm’ we encourage teachers in delivering this lesson to be careful they do not unintentionally:

- Reinforce negative stereotypes about the global south.

- Ignore the existence of poverty and inequality in Scotland.

- Leave learners with a sense of helplessness, that there is nothing they can do to fight poverty.

- Ignore poverty and inequality within the UK.

- Leave learners thinking Africa is a single homogenous country.

- Unhelpfully simplify complex subjects.

- Unfairly demonise one celebrity or one charity when the issue is wider and societal.

- Discourage learners from donating to charity appeals or getting involved in international links.

- Encourage ‘white saviour’ ways of thinking: that richer countries can and should set out to ‘save’ poorer countries (see our separate lesson on this topic).

Q – What is your first thought when you think of ‘Africa’?

Ask learners to draw their first image that comes into their head when they think of Africa.

Q – What aspects of this image are positive and what are negative?

Without changing the content of their pictures, invite learners to annotate on to their drawing labels highlighting what they see as negative/undesirable aspects of their picture (e.g. ‘poor’, ‘dirty’, ‘sick’), and then label any aspects they see as positive (e.g. ‘beautiful landscape’; ‘wildlife’ etc). Try not to influence learners, instead encouraging them to honestly reflect on what they first drew.

Q – Do you think all of Africa is like your picture?

Ask learners this question and facilitate a discussion around this. Try to bring out the below points:

- Africa is a continent made up of 54 countries, each of which are different. Just one of these countries, Algeria, is 80 x bigger than Scotland by landmass (2.38 miles2, compared to 20,081 miles2).

- There are over 1.4 billion people in Africa, and over 2,000 languages.

- Yes, many parts of Africa are extremely poor compared to Scotland but, just like Scotland, countries in Africa have rich people and poor people; there is diversity and inequality.

Q – Where did you ‘get’ your image of Africa from?

Ask everyone who has not been to Africa to put up their hand. Invite these people to share where they learnt about Africa / where they got this image from (e.g. a charity appeal, the news, a wildlife documentary, etc)

Q – Are images ‘neutral’?:

Facilitate a discussion with learners around this question, trying to bring out the following point:

- Even photos and ‘real’ video aren’t neutral: someone has chosen what to photograph, from what angle, to tell the story they want to tell (the image might be a true likeness of something but the story, or ‘narrative’, might be made up).

Q – Why do some media sources want to give us certain narratives of Africa?:

Facilitate a discussion, encouraging learners to think about each of the below, asking them why this media would tell a certain story/narrative of Africa. Encourage learners to think about the context for each:

- Who is ‘producing’ the narrative and who is ‘consuming’ it?

- What intentions do the producers have – what do they want people to do when they watch?

- What is the historical context?

- What assumptions might there be?

- What is the impact of their narrative?

- News report – Will always want to focus on the newsworthy story – the war zone, the area in drought or famine, the corrupt politician. It isn’t a proportionate representation of life in Africa but rather what’s going wrong in Africa. Most media outlets have a commercial incentive: they need to sell more papers, or get more advertisers. This can have a negative consequence: with people consuming this news thinking this is what all of Africa is like.

- Charity appeal – Often charities give us a negative image of Africa (starving children, etc) to encourage people to donate. Sometimes they can be guilty of a ‘white saviour’ mindset (benevolent white people have the skills, capabilities and duty to ‘save’ Africa) which comes from generations of colonial rule. There can be an assumption that the more shocking the image, the more money will be donated. This can have negative consequences as the audience becomes used to associating ‘Africa’ with ‘pity’ and ‘unending poverty’.

- Films (especially older films) – Often showed Africa as ‘dark’, ‘dangerous’, ‘wild’ and ‘exotic’, while white involvement was often seen as ‘romantic’, ‘heroic’, ‘elegant’, ‘brave’, ‘beautiful’ and ‘doing good’. Such stereotypes were often directly racist and historically served to justify colonial rule. They have had hugely damaging consequences. [Slide: The African Queen (1951) Out of Africa (1985) Blood Diamond (2006) ]

- News report – Will always want to focus on the newsworthy story – the war zone, the area in drought or famine, the corrupt politician. It isn’t a proportionate representation of life in Africa but rather what’s going wrong in Africa. Most media outlets have a commercial incentive: they need to sell more papers, or get more advertisers. This can have a negative consequence: with people consuming this news thinking this is what all of Africa is like.

Sometimes negative images and narratives in the media are created intentionally with a purposeful negative agenda and are easy to spot, and sometimes they are not intentional and are harder to spot. Either way, they often come out of ignorance (made by people that haven’t been to Africa), laziness (it’s easier to perpetuate stereotypes than challenge them), assumptions and racism.

- Images and narratives are almost never neutral, they are produced to tell a certain story, and usually make one group of people look good and others look bad.

- Many portrayals of Africa in the media, even the news, include harmful negative stereotypes.

- It is important to be alert to what sort of narratives you are consuming, from where, what agendas and stereotypes there might be and what the historical context is.

Watch the BBC clip of Rab C. Nesbitt.

Q - How were Scots portrayed in this programme?

Ask learners to describe in one word how Scots are made to look in this clip, first asking for negative points (drunk, violent, all white, poor, rude, uncultured) and then positive points (not many!).

Q – Is this a fair image of Scotland and Scots?

Facilitate a discussion, drawing out points around the diversity within Scotland.

Q – What other stereotypes about the Scottish can you think of?

Facilitate a discussion, perhaps drawing out points like: bagpipes, red hair, kilts, miserly/ungenerous, tartan, whisky, deep-fried mars bar, bad weather, bad food, Loch Ness Monster, angry and unwelcoming, Haggis.

Ask if these are all true and where learners feel these images of Scotland came from.

Q - How do these Scottish stereotypes make you feel?

Encourage learners to think about feelings empathy, to build their understanding of how others feel when stereotypes are perpetuated in the media about them.

Stopping to think ‘how would I feel if this were the other way round’ is one of the most important ways you can judge whether you’re doing the right thing. This is called ‘empathy’ and its hugely important.

Q- What does Scotland need other countries to do, for Scotland to get richer, and do these stereotypes help?

Scotland needs other countries to: buy Scottish goods, trade with Scotland, invest in Scotland and visit Scotland.

Negative stereotypes make it less likely that others will see you as an equal: they are less likely to do business with you or go on holiday to your country if they do not feel confident and safe.

The same is true of negative stereotypes about Africa: they make it less likely that others will trade with Africa, invest in Africa, buy African goods and visit Africa on holiday.

- There are negative stereotypes about Scotland just as there are about Africa.

- It isn’t nice to have negative stereotypes and narratives about you in the media – it leads others who haven’t met you to make negative assumptions about you.

- Negative narratives can have real, harmful negative consequences for whole countries and continents – this can mean poor countries get poorer.

View the slides showing images of charity appeals with negative stereotypes.

Q – What is the narrative in these appeals?

Listen to learners and encourage them to think about:

- Who produced them? [A charity raising money]

- Who ‘consumes’ them? [People in the UK who probably haven’t been to Africa]

- What do they want the ‘consumers’ to do? [Donate money]

- What narrative do they tell of people in poorer countries? [Poverty, pity, hopelessness, needing saving]

- What narrative do they tell of people in richer countries? [Kind, generous, have a duty to ‘save’]

- What impact does it have overall? [Continues stereotypes, makes sustainable economic development in these communities harder].

Q – Does raising money for a charity justify using negative narratives?

This is a complex area. Perhaps break the class in two and debate the question, to ensure both sides of the issue are aired.

- On one side:

- If there is a crisis humanitarian situation is it not right to show what this really looks like.

- Are these appeals trying to represent specific crisis situations, not all of Africa?

- Would anyone that had their lives significantly improved really question a narrative of pity used in a video 5,000 miles away, if this is what generated the necessary funds?

- Is our concern with these images really about just not wanting to others’ suffering?

- BUT on the other side:

- think about the dignity of those portrayed.

- think about the longer term, wider impact of negative narratives on trade, business, investment and tourism.

- Even if these appeals only aim to raise awareness of one crisis situation, if this is all audiences see of Africa, then this is the image people are left with of Africa.

- what harm does it do to have audiences become used to, and desensitised to, negative images like this: do they see certain parts of the world as ‘hopeless’ and ‘permanently poor’?

- what harm does it do the communities themselves, to have photographers and videographers turn up and want to show suffering, so others can ‘save’ them?

- Are there better ways to raise funds, which don’t require the same negative images?

Watch Radi-Aid by the Norwegian Students' & Academics' International Assistance Fund (SAIH).

Q – What reflections do you have from this video?

Encourage learners to think about what the video is about and for.

It is a parody video, making fun of and questioning celebrity-led music videos which raise money for Africa which can be underpinned by assumptions and negative stereotypes. It turns this on its head by imagining Africa raising funds for Norway to buy radiators.

Explain that this video was made by the Norwegian Students' & Academics' International Assistance Fund (SAIH). This is an organisation which is committed to challenging negative stereotypes in international development.

Explain that, inspired by this video, they used to have an annual competition to highlight charity videos which they thought have harmful narratives and negative stereotypes to encourage a critical understanding of this issue. The Comic Relief video shown received their ‘Rusty Radiator’ award.

They also had a ‘Golden Radiator’ award for charity videos which had more positive narratives and which challenged stereotypes. Here is one of the winners:

Q – What reflections do you have from this video?

- Who is the ‘hero’ of this story?

- What stereotypes is this video challenging?

- How does it make you feel?

- What does it make you want to do?

People watching this video see the ‘hero’ is the dad: they can imagine what it must feel like to go through a war, perhaps because some can remember the time they thought their dad was invincible.

It is moving but it doesn’t reply simply on pity, poverty and vulnerability: it offers empathy and insight. It challenges negative stereotypes about refugees and asylum seekers.

Recent research has shown that, if done well, like this video, charities can use more positive, honest narratives of Africa and still raise the same amount of money, or even more.

Q – What can YOU do to ensure you’re not consuming or sharing negative stereotypes?

Facilitate a discussion, trying to draw out the below points:

- Think about the media and narratives you are consuming: who is making them, who is consuming them, what are the assumptions and stereotypes, and what harm might this be having.

- Look for different media and different sources of information on this subject. If you want to learn about Malawi, try to find a Malawian source (if someone wanted to learn about Scotland, you would want them to ask someone from Scotland).

- Think about your own word and actions. We have focused mostly on film, tv and the news but social media is possibly a more important source of negative narratives because it isn’t regulated and you can’t see what messages different people are receiving. Every time you ‘like’ or ‘share’ something, you are responsible for passing it on: before you do, ask if you’re sure it is true, fair and constructive, ask yourself how you would feel being portrayed this way.

- Charities using negative stereotypes in the narratives they create can have a lasting negative impact, even if they use these narratives to raise funds and do good.

- Things are changing, and more and more charities are choosing to use more positive, honest, diverse and dignified narratives, while still raising the same amount of funds, or more.

- It’s important to think about the media and narratives you are consuming; try to listen to different voices (most importantly people from the countries you are learning about); and take responsibility for what you consume and share on social media.

The case for Climate Justice

This session looks at the real, human impact of the climate crisis in Malawi, now and in the future. It compares the likely impacts in Malawi and Scotland, and compares the relative contribution which each nation has made to causing the climate crisis in terms of carbon emissions. It takes a social justice approach, highlighting both instances of positive cooperation between Scotland and Malawi in the area of climate justice, and instances where the global north has repeatedly failed to deliver pledges for such support.

| Learning outcome | Learning intention |

|---|---|

| Understands some of the current, and likely future, impacts of climate change in Malawi, and how this compares with Scotland. | I can see how the climate crisis will affect people in Malawi and Scotland differently |

| Understands how little Malawi has done to cause the climate crisis and sees the injustice in this | I see how unfair it is that Malawi hasn’t caused the problem but will suffer the most |

| Understands and can define ‘climate justice’ | I know what ‘climate justice’ is |

| Understands and values climate action through partnership and solidarity but recognises much more is needed at a higher level | I can see that good things are happening between Scotland and Malawi to fight the climate crisis but we’re not doing enough |

Teacher notes: Introduction to this session:

We appreciate that both you and your students will have an idea of what climate justice is and what it means. The intention here is to provide resources that will assist you in contextualising what climate justice means to your school partnership. What does the fight for climate justice look like and mean to students living in Scotland and to those living in Malawi? What are the similarities and where is the common ground? How can your partnership support one another to ensure that climate justice is addressed and tackled in a constructive, positive way. We appreciate that you are the experts in terms of answering these 'wicket problems' and therefore we rely on you to feedback to us at the SMP so we can ensure our resources are as relevant and up to date as possible.

As with all of the critical learning resources, there are no ‘right answers’ here. However, we firmly believe that through discussion and dialogue a deeper understanding and confidence can be achieved.

This is a hugely important area but we recognise it is complex, sensitive and important to get right. As presented here, it is most suitable for upper-secondary but many aspects of this lesson could be adapted for different age and stages.

This resource is made up of four sections:

- Climate Change in Scotland and Malawi.

- Malawi’s Impact on the climate.

- Defining Climate Justice.

- Climate Action

Depending on the age level and amount of discussion, one section can lead on to the next within one lesson period. Alternatively, each section can be used separately as individual discussions.

The key learning outcomes are in a text box at the end of each section, so you can pick and choose.

The sections are framed around class discussions. There are also several short online video links to trigger discussion.

We’re here to help, so if you want any support, advice or even someone to come and deliver this lesson for you, please just email youth@scotland-malawipartnership.org.

Do No Harm:

In keeping with our principle of ‘do no harm’ we encourage teachers in delivering this lesson to be careful they do not unintentionally:

- Reinforce negative stereotypes about the global south.

- There are signs of renewed associations between African countries with ideas of vulnerability and fragility. Climate anxiety and persistent associations of children with poverty threaten to undermine attempts to dissociate Africa from vulnerability and fragility. Representations of African countries, people and themes in these contexts tend to perpetuate the idea that Africa and Africans are in need of saving, rather than fellow agents in combatting these issues. From the New Narrative Report – March 2020 M&C Saatchi world services - British Council

- Leave learners with a sense that all interaction between the global north and the global south are inherently questionable – this is not the case.

- Leave learners scared to engage internationally for fear of being called out or getting the language wrong – it is important to speak of the benefits of internationalism and global citizenship.

- Deny that extreme poverty exists in countries like Malawi, that there is significant social injustice in the inequality between countries like Scotland and Malawi, and that there is crucial value in working together with countries like Malawi to call this out and look to reduce these inequalities

- Encourage unnecessarily hostile, combative or uncompromising attitudes towards others, even those which might be guilty of elements of climate change deniers. Rather, look to build a depth of critical understanding, showing the complexity and encouraging learners to think of ways to challenge and change which are constructive and empathetic (discussing not shouting!).

- Add to Climate Anxiety. Remember to finish all discussions on a positive tone and focus on what positive actions are being taken and how to contribute to this change.

Facilitate a class discussion around the questions below, looking to draw out the following points.

Q – What are some of the effects of Climate Change and their impacts in Scotland?

Current effects:

- flooding,

- rising sea levels,

- damage to buildings and infrastructure,

- increased pests and diseases,

- warmer and wetter winters

Impact:

- we will lose homes and businesses,

- lose many types of plants and animals,

- people will be disrupted from going to work so we could have issues with shops having food, petrol and clothing to sell

- Our lives, towns and cities are not built to run without these reliable sources

Q – What is are some of the effects of Climate Change and their impacts in Malawi?

Current effects:

- droughts,

- flooding,

- shorter growing season,

- changeable weather so harder to grow food

Impact:

- 90% of Malawi’s population relies on farming for an income, the climate change can make it impossible to grow crops. .

- Reduced ability to grow food

- Hunger, 29% of Malawi’s population already live in extreme poverty. (This could lead into further discussion about poverty in both Scotland and Malawi, does climate change have an impact on this Scotland)

- Spread of disease

- Reduced power and fuel supply

- Leads to more even more poverty, ask the class why they think this happens.

Watch: How one of the world's poorest countries is bearing the brunt of climate change | ITV News

From October 2021.

Q - What are your main take aways from the video?

- What are you surprised at?

Q - Whose fault is it that Malawi’s climate is changing?

- The reporter states that, “Malawi is caught in a cycle of destruction. Some of it self-inflicted.”

- Why do you think is meant by this?

- Is it fair? Why or why not?

Q - Which country do you think climate change has a greater effect on?

- Climate change has had an effect on both countries but the severity is different due to each nation’s ability to adapt.

Q - Is the climate crisis our own personal fault?

- Yes and no. The global north is responsible for the majority of climate change due to industrialisation and its consumer practices. Generationally, the fault can be placed on those before us. However, this does not change the reality of the present and action is required by everyone today if the climate crisis is to be tackled.

Additional resources pertaining to Malawi’s climate crisis:

Alarm as Malawi's Lake Chilwa threatened by climate change -https://youtu.be/sihsOmWaX6I

- Understand that Scotland and Malawi’s climate crisis has several similarities.

- Understand that the severity of climate change differs due to economic and political reasons.

This section explores and demonstrates both the UK and Malawi’s global emissions and their relative impact.

Watch the following video, 'A Short History of Global Emissions from Fossil-Fuel Burning (1750-2010)'.

Rewatch and ask students to focus on the UK and Malawi on the map. Pause the video at approximately 0:25 (1967). Malawi is visible only by identifying Lake Malawi. What differences do they notice in terms of fossil-fuel burning activity.

By following this link, the class can explore the timeline and see the UK’s percentage world share of emissions: Global Historical Emissions Map (aureliensaussay.github.io)

Share this website which uses an animated, distorted, shaded, interactive map to help convey how different countries fit into the climate change picture – both the causes and the risks.

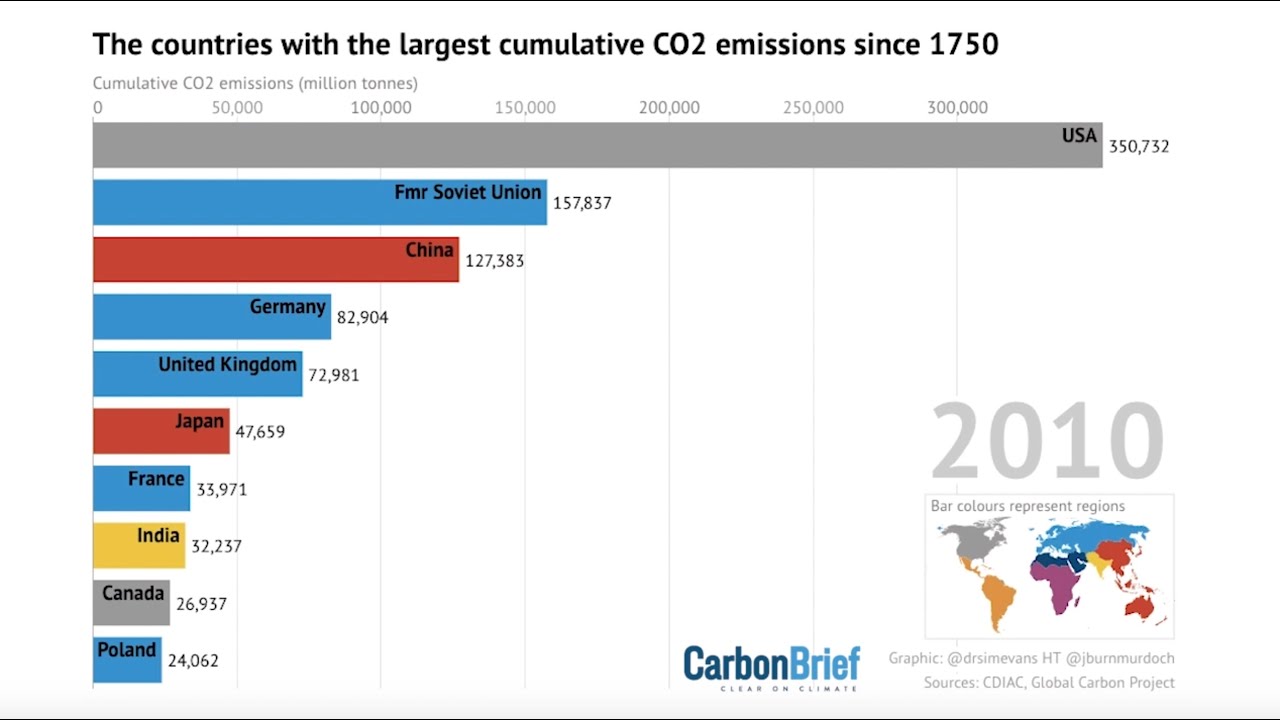

Finally, watch this video to see a bar chart race of the countries with the largest cumulative CO2 emissions since 1750.

Q - Which country has omitted more CO2 into the atmosphere?

- Scotland and the UK have contributed far more

Q – What are the major differences between Scotland and Malawi’s historical development in terms of carbon emissions?

- Industrialisation

- Deforestation

- To realise that the global north has contributed the majority of carbon emissions to date.

- That despite not contributing to the climate crisis, Malawi is experiencing severe effects from it.

Q – What do you think Climate Justice means?

- Explore what climate justice means to students based on what they have previously learnt or have heard in the news

Climate justice is a concept that addresses the just division, fair sharing, and equitable distribution of the benefits and burdens of climate change and responsibilities to deal with climate change.

Watch the video below, 'Climate Justice According to a Kid'.

Q3 – Should the global south be expected to address the climate crisis in the same way as the global north in terms of carbon reductions and adoption of green technologies?

- Is it fair or even realistic for nations not responsible for the climate crisis to fix it?

- After students have discussed the question, what the video below.

In the below perspective-shifting talk, energy researcher Rose M. Mutiso makes the case for prioritizing Africa's needs with what's left of the world's carbon budget, to foster growth and equitably achieve a smaller global carbon footprint.

Additional resources

Exploring Climate Justice: A human rights-based approach

Climate Justice Education — IDEAS (ideas-forum.org.uk)

This resource has been developed as a partnership collaboration between WOSDEC, the ThirdGeneration Project, the Royal Society of Chemistry, ScotDEC, and Eco Active Learning, with the assistance of Oxfam through the European Union.

Keep Scotland Beautiful

second-level-climate-justice.pdf (keepscotlandbeautiful.org)

This learning journey explores climate justice in the context of the Scotland Lights up Malawi Project. Through exploring and investigating different sources of evidence pupils will be able to compare and contrast Scotland with Malawi to develop reasoned and justified views on issues surrounding climate justice.

Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund (SCIAF)

Climate Justice: Called to Care for Creation (sciaf.org.uk)

This resource provides learners with the real-life perspective on the effects of climate change on people and planet. It shares the voices of SCIAF partners who live in the world’s poorest countries, and who are most affected by climate change, but have done least to cause the problem.

‘While 91% of farmers in the US have crop insurance to cover losses in the event of extreme weather, only 15% of farmers in India are covered, 10% in China and just 1% or less in Malawi and most low-income countries.’ - Oxfam 2015 - mb-extreme-carbon-inequality-021215-en.pdf (oxfam.org)

‘Climate vulnerability: as the world becomes increasingly cognizant of the threat of climate change, historical associations of African countries with precarity have begun to take on a new form. As a result, the focus tends towards representations of African countries as subject to disasters caused by climate change, rather than on the leading role of young Africans in helping to combat a global challenge.’ - New Narratives Report, 2020 new_narratives_report_0.pdf (britishcouncil.org)

Q - What can I do?

- This is where dialogue with your partner school is vital.

- What issues are most affecting your partners?

- What actions have they tried to take?

- What campaigns and actions can your school partnership take?

- Is tree planting, recycling and active transport enough to save the planet?

‘The discussion we had about climate change was quite eye-opening as despite living on the otherside of the world, our partners for the storytelling session still worried about

issues like climate change just as we did. Before the session I hadn’t realised climate change was a problem in Malawi but hearing the impact that deforestation can have on communities completely changed my views.’ - Feasibility Study report | steka (stekaskills.com)

Related resources and articles on Climate Action

Friends of the Earth International

Watch our animation to understand how the dirty energy system is at the root of climate injustice. The solution? No more dirty energy, we need an energy revolution now. Join us www.foei.org

https://youtu.be/lOKvBF_4n4g

Global Climate Emergency - Do Nothing or do Net Zero?

Climate Emergency | Net Zero Nation

8 Empowered Ecofeminists Fighting for Justice (healthline.com)

Oxfam

Take action for climate justice | Oxfam GB

Aimed at teachers and educators, this short guide is packed with practical advice, classroom activities and helpful planning tools to inspire young people to take action for climate justice at school.

- That students can identify actions that they can personally and as a school partnership take that will have a positive step in addressing the climate crisis.

- Students appreciate the value of co-creating actions with partners that are based on shared concerns and aspirations.

Understanding Malawi: its language and culture

This session looks to start building an understanding of Malawi, with basic insight into: where Malawi is; the Malawian flag; the currency in Malawi; traditional Malawian dress; as well as shopping and food. It teaches a few basic greetings in Chichewa. But, before this, the session takes time to explore what ‘culture’ means, discussing the complexities and sensitivities, encouraging empathy, and giving practical advice about how to avoid harmful stereotypes when discussing a ‘national culture’.

| Key learning outcomes | Learning intention |

|---|---|

| Recognition of the role of culture and the importance of avoiding stereotypes | I understand that it’s important to respect different cultures and can imagine what it is like to be stereotyped |

| Basic insight into some the cultural differences and similarities between Scotland and Malawi | I can see that, in some ways, life in Malawi is quite different to life in Scotland, but in other ways we’re much the same |

| Able to say a few words or phrases in Chichewa | I can speak a little of one of Malawi’s languages |

Credits and useful resources

Book: Malawi - Culture Smart!: The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture, Kondwani Bell Munthali

Book: Malawi Bradt Travel Guide, Philip Briggs

YouTube: Learn Chichewa : Lessons for Beginners

Book: Chichewa 101 - Learn Chichewa in 101 Bite-sized Lessons

Online Chichewa - English Dictionary

AFS Intercultural Programs briefing on generalisations and stereotypes

Teacher notes: Introduction to this session:

This webpage gives you all need to know deliver a lesson introducing aspects of Malawi language and culture.

The resource can be developed and adapted in many different ways and we encourage teachers to think innovatively and adapt as they see fit.

Key terms you may wish to define and ensure are understood, include: “culture”, “stereotype”, “diversity”, “generalisation”, “empathy”, “continent” and “land-locked”.

The resource is split into two sections. The first is a discussion-led exercise to understand what culture means and to bring out the risks of reinforcing negative stereotypes when talking about a nation’s culture. Encourage empathy: helping learners really think about how they feel when others make assumptions and stereotypes about them.

There is an accompanying PowerPoint which we recommend teachers use, especially for the second half of the resource. It has embedded sound files to help with pronunciation and teacher notes.

We’re here to help, so if you want any support, advice or even someone to come and deliver this lesson for you, please just email youth@scotland-malawipartnership.org.

Do No Harm:

In keeping with our Partnership Principle, ‘do no harm’ we encourage teachers in delivering this lesson to be careful they do not unintentionally:

- Reinforce negative stereotypes about the Malawi and the global south.

- Leave learners with the belief that all Malawians share exactly the same culture or language.

- Unhelpfully simplify complex subjects.

- Encourage social othering and language of “them” and “us”.

Explain to learners that before learning more about Malawi’s language and culture, it’s first important to explore a bit more about ‘culture’, what it means, why it’s important and how to avoid reinforcing stereotypes when talking about culture.

Q – What is ‘culture’?

If learners struggle to give a definition of the word, try starting by asking for examples of culture and work backwards from that.

Here are just some of the many different definitions of culture include:

- the ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a particular people or society.

- the characteristic features of everyday existence (such as diversions or a way of life) shared by people in a place or time